Rek-O-Kut T12h Turntable

Barking Mad?

Sometimes I think to myself, ‘Greg, you’ve gone ‘round the bend on this one,’ usually about the time I try to explain to my better half that I’m working on some exciting, often grandiose new plan for improved fidelity. Without even looking up from her iPad, she sighs and distantly replies, ‘OK. Sure. Go ahead…if that’s what you want…’

Sometimes I think to myself, ‘Greg, you’ve gone ‘round the bend on this one,’ usually about the time I try to explain to my better half that I’m working on some exciting, often grandiose new plan for improved fidelity. Without even looking up from her iPad, she sighs and distantly replies, ‘OK. Sure. Go ahead…if that’s what you want…’

A case in point: I’ve had a relatively recent fascination with monaural playback and putting together a turntable specifically to spin those old records. Not satisfied to have one working turntable with a jack-of-all-trades cartridge, or even one table with two arms carrying more specialized cartridges, or even a mono button on my preamp, I had to go and build – build, not buy – a second table specifically to for monaural playback.

Of course, where hi-fi is concerned, “buy” is bound to raise its head. Late last year I decided I needed to find something productive to do to stave off the boredom of cabin fever as we hunkered down for a long Winter. Fortuitously, at about the same time, I won an eBay auction for a very clean looking, unrestored Rek-O-Kut T12h idler wheel broadcast turntable for a whopping $167. Not bad considering in 1952 it retailed for $119.95.

My entire system is built around opportunistic bargains – one-third off discontinued models, that sort of thing – but this was a cheap piece of equipment even by my standards. But like anything else in hi-fi, that initial expense was just the tip of the iceberg. I bought a tonearm, then a second tonearm that I liked better than the first one, had the motor rebuilt, sent the idler wheels out to be re-surfaced, had the swing-arm machined out of solid brass, purchased a table-saw (vintage, of course) so I could cut the lumber for the plinth, as well as a belt sander to make it smooth, then glued, sanded, clamped, stained, varnished, and tweaked…well, you can see where this is going…

It’s a good thing I’m not paying myself union scale.

By the time I was done building this thing I could have purchased a gently used VPI or another Sota, or some other such high-quality modern turntable. But anyone can do that. This route was much more fun, and my efforts yielded a functioning turntable that’s truly unique. Was it worth all that trouble? Well sure, if nothing else at least in personal satisfaction.

Spin It Like a Caveman

The Rek-O-Kut T12h was in production from approximately 1948 to 1955 – we’ll call that the middle-ages in hi-fi history – and was the predecessor to the far more widely known, but not nearly as impressively built, Rondine B12 units (I have one of these as well for comparison). The various Rondines were available as consumer models and there were a lot of them built. The T12 variants were generally for the pro market and are far less common as a result.

Like other American-Made professional transcription tables of the era, including RCA, Collins, Gates and the like, the T12h utilizes an idler drive mechanism. There is no belt or direct drive. Instead, the motor shaft engages with a rubber wheel which in turn engages the inside rim of the platter to make it spin. When the T12 was built idlers were common, but they faded during the 1960s as belt-drive and then direct-drive took over the consumer market. They hung on tenuously in radio stations – they’re good for back cueing – until the advent of the compact disc killed them off for good. The radio station where I DJ’d in college still had eight Sparta idlers well into the mid-nineties.

When new, the T12h was sold as mechanicals-only. The user had to supply a base and tonearm and also had to figure out how to install all those pieces properly. It was among the first turntables marketed as meeting the National Association of Broadcasters standards for speed regulation and WOW. There were several versions of this mechanical system including a full cutting lathe and a 16” platter version. The manual itself, available for download on Vinyl-Engine, is six typed (with a real typewriter) pages with hand-drawn diagrams describing bearing installation, lubrication, and operation.

One major difference between this table and the other American broadcast idlers is that it’s very compact. Other functionally comparable tables were built into large top-plates with the tonearm mounted directly to the plate. By contrast, the top plate of the T12h measures only nine by eleven inches with the main bearing and platter offset to one corner. The platter radius arcs completely over the right and rear of the top plate, requiring the user to mount the tonearm directly to the plinth. Alternately – and this is the route I chose – one could utilize some form of external arm board.

As originally delivered the T12h supported 78 and 33 RPM records, with a 45 RPM replacement idler wheel available later as seven-inch singles hit the market. Mine had the 45 RPM wheel installed when it arrived. The wheels themselves are two-layer wedding cake style, with the lower, wider portion contacting the motor spindle and the smaller upper portion in turn engaging the platter.

A Very Small Battleship

They don’t build ‘em like this anymore. No one builds anything like this anymore.

Everything on the T12h is milled from substantial aluminum bars or castings, likely by hand before computerization. The material exception is the well for the main bearing which is a three-inch slug of steel that still bears the indented scars where it was clamped in place to be bored out to accept the 3/4” diameter main bearing spindle. The spindle spins on a 1/4” ball bearing that sits in the bottom of the well. Three quarters of an inch is a *big* bearing spindle. There are a few other tables with bearings that large, but not many. On this turntable the spindle has a precisely cut spiral groove wrapping around it, carrying oil up the side and ensuring that everything remains well lubricated. The milling tolerances are tight enough that lifting the platter creates significant suction. It requires some force to separate the bearing from the well.

As I progressed with the rebuild, I was pleased to find was how well constructed and easy to work on this turntable is. The machine screws and sockets are precise, and there were few if any rough casting edges. All that’s required to tear it all down and put it back together is a basic set of hand tools: screw drivers, a couple of box wrenches, and pliers. In fact, during this restoration I took the entire thing apart three times. The first for the initial rebuild, again when I decided that the motor really did need professional attention, and then finally a third time when I removed the mechanicals from the top-plate so I could add damping material. It’s a very easy turntable to work on: simply designed, well thought out, overbuilt and effective

In keeping with the overkill/over-built theme, the motor is the size of a small coffee can. Rek-O-Kut installed several motors on this table, but this one is an 1800 rpm Elinco unit that’s a full four inches in diameter and six inches tall. Installed, it hangs seven inches down from the top plate necessitating a very tall plinth to hide it completely. It too is made of cast aluminum with two brass spouts to periodically add a few drops of oil. When I took it to a local electric motor repair shop (itself a seventy-year-old anachronism) they were incredulous that a motor this large had come out of a mere record player, though after rebuilding it they also pronounced it to be of excellent quality. The motor is hard-wired to a standard, ungrounded two-prong electrical plug – four internal wires in total between the plug, switch and motor. There are no circuit boards, servos, or other electronic do-dads, just a single large capacitor that acts as a spark suppressor (the subsequent Rondines got really fancy by adding two more wires for a pilot light). Following the rebuild the motor gets the platter from zero to full speed in about one-quarter of a rotation and it’s all but inaudible in any practical sense. If a soft whirring noise that can only be heard when you’re standing right over it is a deal-breaker, this isn’t the turntable for you.

In keeping with the overkill/over-built theme, the motor is the size of a small coffee can. Rek-O-Kut installed several motors on this table, but this one is an 1800 rpm Elinco unit that’s a full four inches in diameter and six inches tall. Installed, it hangs seven inches down from the top plate necessitating a very tall plinth to hide it completely. It too is made of cast aluminum with two brass spouts to periodically add a few drops of oil. When I took it to a local electric motor repair shop (itself a seventy-year-old anachronism) they were incredulous that a motor this large had come out of a mere record player, though after rebuilding it they also pronounced it to be of excellent quality. The motor is hard-wired to a standard, ungrounded two-prong electrical plug – four internal wires in total between the plug, switch and motor. There are no circuit boards, servos, or other electronic do-dads, just a single large capacitor that acts as a spark suppressor (the subsequent Rondines got really fancy by adding two more wires for a pilot light). Following the rebuild the motor gets the platter from zero to full speed in about one-quarter of a rotation and it’s all but inaudible in any practical sense. If a soft whirring noise that can only be heard when you’re standing right over it is a deal-breaker, this isn’t the turntable for you.

The motor is suspended from four rubber grommets, which are still produced by the Lord Corporation and readily available. Variations on this grommet-based suspension system were used on Rek-O-Kut models for decades and replacement of those rubber bits is mandatory on almost any restoration. The originals have a tendency to harden into a crumbling brittle mess that in this case took hours to scrape off the mounting plate. When they’re functioning properly they’re designed to decouple the motor from the rest of the turntable, eliminating any direct mechanical connection.

The grommet-based suspension is one area I’m still wrestling with. The flaw in this design is that, while Rek-O-Kut seems to have used just one value of grommet in all of its turntables, that one grommet suspended a variety of motors of varying weights. As the motors get heavier the ability of the grommets to quell vibrations decreases, and the Elinco motor is among the heaviest motors Rek-O-Kut used. As a result, the grommets in this application have trouble keeping the motor perfectly still. The motor spindle vibrates a bit as it drives the idler wheel resulting in a bit of unwanted sonic wobble, primarily audible on piano records. It’s gotten better as I’ve continued to tweak it, but as I write this I’m still experimenting with ways to quell that unwanted motion, including alternate parts. I may even build a whole new plinth specifically to address this issue, you know…in my spare time.

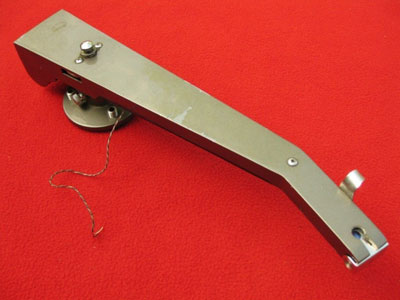

Aside from the nine-layer birch-ply plinth, the final piece of the build was a swing-arm on which to mount the tonearm. Depending on how it’s positioned a swing arm can accommodate pretty much any arm between nine and twelve inches long simply by turning it to the appropriate pivot to spindle distance. On this turntable I’m using a twelve-inch arm and all that was required set it in place correctly was 270 mm jig. Turn the swing arm to meet the jig and that was it.

I also wanted the highest-mass material I could think of for that swing arm. Depleted uranium wasn’t readily available so I settled on navy brass milled into a 1” x 3” x 6” soap-bar with threaded mounting holes tapped into it. A friend who has access to a CNC machine cut it and the finished product weighs in at about six pounds. It attaches to the plinth with a bolt and cam lock. If there’s any vibration traveling through that big brass bar, I can’t hear it.

Twist My Arm

As we rolled into 2018 I was still missing a suitable tonearm. My initial intent was to get something familiar like a Jelco SA-750, one of the great bargains in hi-fi and the arm that’s installed on my Sota. But aesthetically that didn’t seem like a good match for the Rek-O-Kut. The Jelco arms scream 1980s – at least to my eye – while the ROK looks like a piece of WWII military surplus hardware. Even something like the chrome of an SME 3009 seemed altogether too flashy, so I began looking at period-correct vintage arms.

The one design I kept coming back to – and I concede, initially just because I think they look really cool – is the Gray Research 108 and its derivations and imitators. If you’ve never seen one, it’s a massive triangular thing that was in wide professional use in radio stations during the 1940s and 50s. These are damped unipivot designs – essentially an inverted cup resting on a pin – with a blob of heavy weight silicone supplying the damping. The early Gray arms are notably crude – typically a single rough cast for entire arm, hollow and unfinished underneath leaving a space for the wires, with a split steel ball bolted in to accept the pin from the base. The typical counterweight is a non-adjustable slug of lead.

The one design I kept coming back to – and I concede, initially just because I think they look really cool – is the Gray Research 108 and its derivations and imitators. If you’ve never seen one, it’s a massive triangular thing that was in wide professional use in radio stations during the 1940s and 50s. These are damped unipivot designs – essentially an inverted cup resting on a pin – with a blob of heavy weight silicone supplying the damping. The early Gray arms are notably crude – typically a single rough cast for entire arm, hollow and unfinished underneath leaving a space for the wires, with a split steel ball bolted in to accept the pin from the base. The typical counterweight is a non-adjustable slug of lead.

Starting down this path, I picked up a very clean Calrad SV-16, a modified, refined Japanese clone of the 108. It’s a definite step up from the actual Gray arms in terms of fit and finish, but it has the same basic operational hazard as the original. The shortcoming of these arms – at least the ones I’ve seen – is that they don’t have any adjustable mechanism to set vertical tracking force. On the Calrad, the lead slug counter-weight is held in place with two fixed screws. Tracking force can be adjusted, but it’s accomplished by adding small brass plates on top of the headshell, which in turn slots into the arm. Users also add weights on top of the arm, either in front or behind the fulcrum, to try to fine-tune the VTF, but it seems painfully imprecise.

Starting down this path, I picked up a very clean Calrad SV-16, a modified, refined Japanese clone of the 108. It’s a definite step up from the actual Gray arms in terms of fit and finish, but it has the same basic operational hazard as the original. The shortcoming of these arms – at least the ones I’ve seen – is that they don’t have any adjustable mechanism to set vertical tracking force. On the Calrad, the lead slug counter-weight is held in place with two fixed screws. Tracking force can be adjusted, but it’s accomplished by adding small brass plates on top of the headshell, which in turn slots into the arm. Users also add weights on top of the arm, either in front or behind the fulcrum, to try to fine-tune the VTF, but it seems painfully imprecise.

As tonearm setup goes, this seems like the mechanical equivalent of adding a few more rocks to the counterweight on a trebuchet. This setup may have been sufficient in the 1950s when people were running Fairchild cartridges at 6 – 18 grams (!) – or during the Crusades when they were flinging boulders at castles – but it seems dubious today given the precision we take for granted as necessary to set up a modern cartridge. (Can you imagine running a needle over an original Lexington Blue Note at 18 grams?!)

There are certainly folks who love the Gray arms and their clones, and use them regularly, but in the end I couldn’t bring myself to give up the control, especially with what is for me is a pretty expensive cartridge like the Miyajima Spirit Mono. I still have the Calrad arm, and I may yet find the ambition to try to set it up properly, but to date I still haven’t heard it in action.

Fortunately, I found another option that’s closely related to the Gray 108 that I was more comfortable with. After a great deal of surfing and lurking on hi-fi message boards I got wind of a small manufacturer located in – of all places – the Ukraine: the Karmadon Unipivot Tonearm, in the twelve-inch version. I’m not going to dwell on the Karmadon arm here because I’ll cover it in a full review, but it too is a damped unipivot arm based on the geometry of the Gray 108, though with a somewhat more traditional look, an adjustable counterweight and a slotted head shell that allows all the basic adjustments for VTF, VTA and even Azimuth, albeit in a relatively simple form. To this I added my Miyajima Spirit Mono cartridge that I bought at Capital Audiofest last November, which I’ll also cover in a more in-depth review.

Fortunately, I found another option that’s closely related to the Gray 108 that I was more comfortable with. After a great deal of surfing and lurking on hi-fi message boards I got wind of a small manufacturer located in – of all places – the Ukraine: the Karmadon Unipivot Tonearm, in the twelve-inch version. I’m not going to dwell on the Karmadon arm here because I’ll cover it in a full review, but it too is a damped unipivot arm based on the geometry of the Gray 108, though with a somewhat more traditional look, an adjustable counterweight and a slotted head shell that allows all the basic adjustments for VTF, VTA and even Azimuth, albeit in a relatively simple form. To this I added my Miyajima Spirit Mono cartridge that I bought at Capital Audiofest last November, which I’ll also cover in a more in-depth review.

Now more or less complete, with arm and cartridge installed and properly set up, this old battleship of a turntable rumbled (colloquially) back into regular use, playing records regularly for the first time probably in decades.

Can You Drive A Stick?

The Rek-O-Kut is an incredibly simple machine to operate because functionally it’s downright primitive. There is no on/off switch. To start it, loosen the single knob – the only control on the turntable – and move it to the right or left, depending on what speed you want, until it hits the stop, then tighten the knob back down. The platter is now spinning. Shifting it into gear does two things simultaneously: it engages the power switch located under the knob, and it moves the entire motor assembly into contact with the idler wheel, which in turn engages the platter and starts rotation. Once it’s running, drop the needle and you’re playing records.

There are also fine adjustments for speed via a setscrew that allows the user to change the pressure of the wheel on the platter, increasing or decreasing the speed of rotation. It works perfectly well.

I’ve also adopted one other bit of startup procedure that’s not in the manual. After it’s been sitting for a few days the oil will drain from around the bearing shaft into the well. If the turntable is started in this condition, the spindle and well sometimes make a little metal-on-metal contact noise for a few rotations until the oil makes its way to the top of the spindle groove. Personally, I think metal-on-metal noises are always the sign of something bad (Go ask Jacob Marley), so to avoid this I pull the platter and bearing shaft three-quarters of the way out of the well, then lower it back in, priming the bearing with oil. I don’t know if that’s strictly necessary, but it certainly can’t hurt, and it does eliminate any scraping.

Does it Sound Like Sonic Nirvana?

The simple answer to that question is, ‘Yes, but…’

The Miyajima Spirit Mono, which is a moving coil, is a very bold and colorful pickup. It sounds great and when set up properly it can be buttery smooth, but it can’t match the treble extension of more modern moving coils like the Audio Technica OC/9-III or AT33sa cartridges that alternate in my stereo rig, but I don’t think it was designed to. On the other hand, with the right monaural recordings it can be more muscular than either of the ATs. Combine that with an arm that’s based on seventy-year-old design parameters, and a turntable that may actually be seventy years old, and the whole thing is a bit vintage sounding, in a good way: smooth, solid, colorful, but without the last word in treble extension or overall detail. But boy, it is musical as all hell.

The Miyajima Spirit Mono, which is a moving coil, is a very bold and colorful pickup. It sounds great and when set up properly it can be buttery smooth, but it can’t match the treble extension of more modern moving coils like the Audio Technica OC/9-III or AT33sa cartridges that alternate in my stereo rig, but I don’t think it was designed to. On the other hand, with the right monaural recordings it can be more muscular than either of the ATs. Combine that with an arm that’s based on seventy-year-old design parameters, and a turntable that may actually be seventy years old, and the whole thing is a bit vintage sounding, in a good way: smooth, solid, colorful, but without the last word in treble extension or overall detail. But boy, it is musical as all hell.

For amplification, I’m using a step-up transformer run into the phono stage in my Cary SLP-98P preamp, a combination that is free of any hum or electronic artifact. I think it’s reasonable to assume that the combination sounds close to what might have been state of the art in the mid-fifties. Considering it was built to play records pressed during that time-period I’d say that’s a successful outcome.

In the time I’ve owned it, I’ve had the Spirit Mono installed in two other turntables: my beater Tech-12 and, for a short period, my Sota Star Sapphire. I don’t think offering a detailed direct comparisons of either table with the Rek-O-Kut is especially valuable. They’re all such different animals that it seems like comparing elephants and fruit flies. However, there are some basic differences.

Briefly, the Karmadon/Miyajima combination – with a much better match of high mass and low compliance, respectively – is a far more compelling pairing than the Miyajima installed on the Mark I Tech 12 with it’s tin no-mass tonearm. The sonic image is significantly larger, the bass is much deeper, and it’s far more dynamic overall, even with the T12’s slight speed instability issue.

The Sota is undoubtedly a smoother, more refined piece of equipment, and that’s audible on playback. But somehow the Spirit doesn’t seem as well integrated with this table. The Jelco arm is a medium mass design and the Spirit is a very low compliance cartridge. Imaging and dynamics seem to suffer a little here as well.

The high-mass Karmadon arm, and the low compliance Spirit cartridge work really well together, which is likely improved with the mass of the arm-board and plinth. Altogether, the Rek-O-Kut and its various components weigh over eighty pounds. The sonic image is clear and dynamic with deep bass, and also quite wide. Sometimes mono records played with a stereo pickup can sound perfectly stacked in a narrow vertical space between the speakers, but that’s not the case here. While it’s very clearly monaural, the sound seems to fill more of the space between the speakers. It’s very natural sounding and a very compelling reproduction of music, even without the endless treble that you can achieve with a more modern moving coil.

It’s also worth noting that the Spirit definitely benefits from as much silicone damping as I can dial into the arm, adding resolution, liquidity and smoothing out the treble appreciably. It took a while to figure out where that sweet spot is, but once I hit it I knew it immediately. Everything just jelled beautifully.

I don’t want to belabor individual recordings, but spinning a ten-inch Ruby Braff record, Ball at Bethlehem with Braff (BCP-1034) it’s clear that it’s a live recording – New Years Eve 1954 – with some room resonance around the musicians. Even without the airy sparkle, the high trumpet notes are all there, bursting with their brassiness, and doing so without ever developing any ear-piercing unpleasantness. Ten-inch records can be hit-and-miss on sound quality. I was pleasantly surprised how good this record sounded and I largely credit the table it was being played on

Turntables Wobble, But They Don’t Fall Down

The one weak spot with this turntable, as I’ve already noted, is a bit of wobble on pianos due to the speed instability. It’s not too bad if the pianist is playing a lot of notes, but any decent pair of ears would likely pick out the vibrato as soon as there’s a note sustained for longer than a second or two. It’s not horrible and it seems to be settling down the more I run the turntable. Anyway, it’s easily overcome with some horns and a rhythm section, though I haven’t found myself reaching for my Bill Evans trio records too often.

That would be a terrible indictment of any modern turntable, to be sure. But the Rek-O-Kut T12h is not modern in any way. It’s sixty or seventy years old, and few of us will be running as well at that age. That it runs at all is a testament to its original build quality. And, as I said, I’m still working on the stability issue and may yet be able to improve its performance.

Most importantly, when the T12h sounds good, it sounds really good. Old Contemporary and Blue Note sides have bass depth and power that was definitely missing when I was using the Tech-12 for a mono rig. Imperfect? Yes. Musically satisfying? Definitely.

Was it Worth All The Trouble?

I didn’t build this turntable with the expectation that it was going to become a state of the art playback appliance. It’s very old and that means coming to terms with some anomalies that you’d never find acceptable in a modern piece of equipment.

On the other hand, the Rek-O-Kut T12h is a lot of fun to use and listen to. It’s a pleasure to operate in the same mechanical way as a good, vintage, manual transmission car: precise, but not too precise, requiring a little skill and practice, as well as a good set of tools.

Aesthetically it’s unlike almost anything else you’re likely to encounter. It looks like a piece of military surplus hardware, and it’s built about as ruggedly. In an age when the vast majority of consumer electronics are largely disposable and often poorly built, this thing looks timeless. ‘Planned Obsolescence’ was not on the specification sheet when this thing was designed. I’m fairly certain that with a little ongoing maintenance this T12h will still be running when I’m dead and gone.

Most importantly, with the good quality mono recordings it sounds darned good. It’s minor eccentricities excluded, it has drive and presence, weight and authority. It’s a little vintage sounding, but it’s compelling and satisfying, and a lot of fun.

And finally, I really enjoyed putting it all together (Three times as a matter of fact). I’m not an engineer, so true electronics – like amplifiers – are beyond my skills. This Rek-O-Kut T12h afforded me the opportunity to actually create a piece I can use in my hi-fi ever day and point to with a sense of personal pride. You could go out and spend fifty grand on a really great state-of-the-art turntable, but you’ll never be able to say that you built it yourself. I can and I really enjoy that.

greg simmons

Specifications:

This is a trick question. There isn’t a list in the original user manual.

Hysterisis Motor with Oil-less wicks

¾” Main Bearing

¼” Ball Bearing

33, 45, or 78 RPM operation depending on installed idler wheels

National Association of Broadcasters certified for speed stability and WOW.

Recommended for ULTRA HIGH FIDELITY amplifiers and speakers systems (from an ad).

Tough as a farm tractor (My own personal opinion)

Seriously, that’s all I’ve got.

One thought on "Rek-O-Kut T12h Turntable"

Leave a Reply

Stereo Times Masthead

Publisher/Founder

Clement Perry

Editor

Dave Thomas

Senior Editors

Frank Alles, Mike Girardi, Russell Lichter, Terry London, Moreno Mitchell, Paul Szabady, Bill Wells, Mike Wright, and Stephen Yan,

Current Contributors

David Abramson, Tim Barrall, Dave Allison, Ron Cook, Lewis Dardick, John Hoffman, Dan Secula, Don Shaulis, Greg Simmons, Eric Teh, Greg Voth, Richard Willie, Ed Van Winkle, Rob Dockery, Richard Doron, and Daveed Turek

Site Management Clement Perry

Ad Designer: Martin Perry

Hi Greg,

In the midst of my own restoration of a Rek-o-Kut T-12…mine is missing the motor. Do you happen to have the Elnico model number? These sometimes pop up on Ebay…

Thanks!!