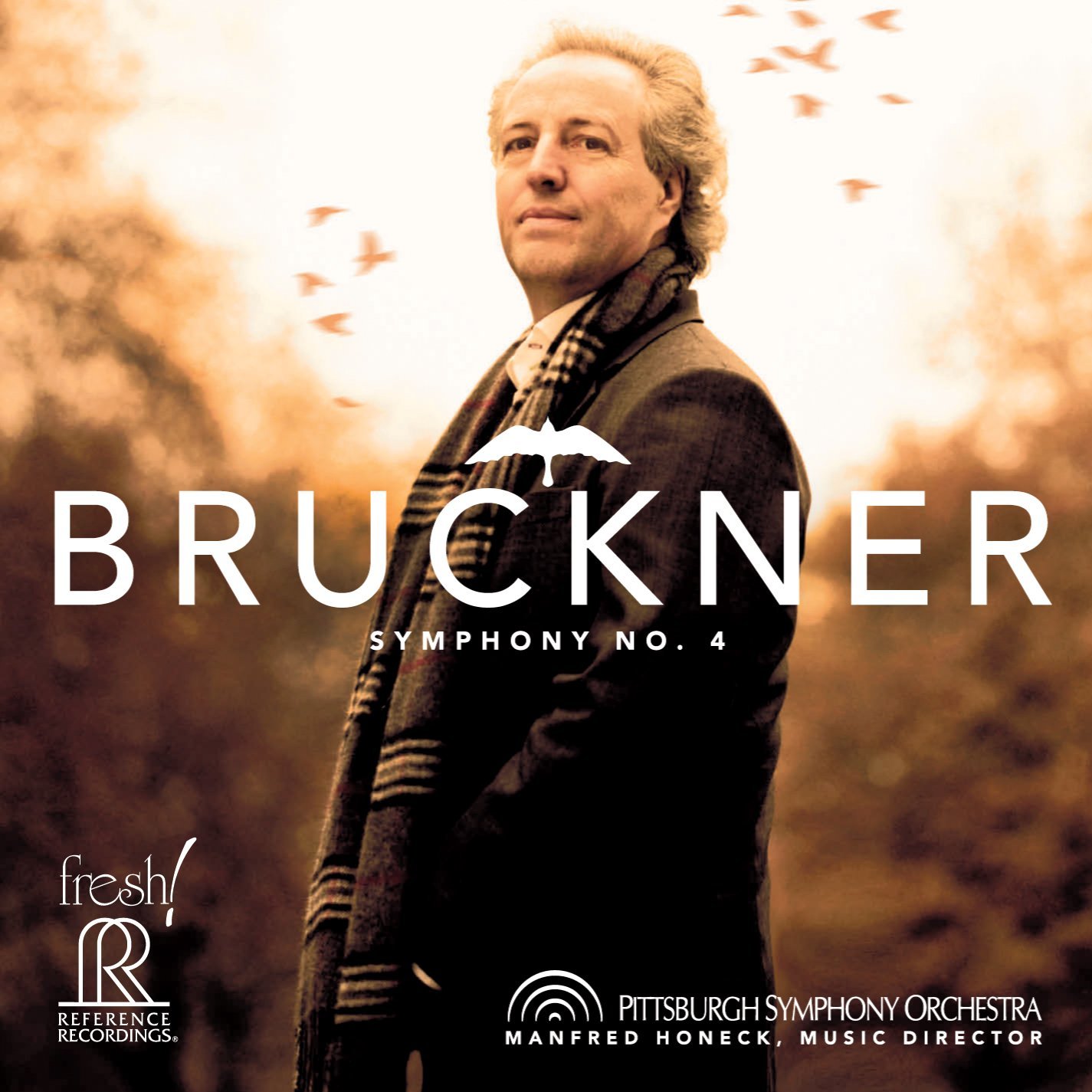

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 4

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 4, Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra conducted by Manfred Honeck. Reference Recordings FR-713SACD

Release of this dual-layer recording (street date February 10) appeared in a publicity email I got from Reference Recordings. I am not one of those music collectors wild for the latest versions simply because they are the latest, but as a Bruckner admirer all my adult life who cut his teeth on van Beinum and the Royal Concertgebouw, I was intrigued by the hoopla.

Reference Recordings is a local company, some forty minutes south of here in San Francisco—perhaps a tad closer to the San Andreas fault than Black Point. They produce CDs of superlative quality—an earlier release of Bruckner’s Ninth with Skrowaczewski and the Minnesota Symphony (RR-81 CD) is a treasured possession. And the early reviews suggested that Manfred Honeck and the Pittsburgh Symphony’s performance is something out of the ordinary. I really did not know the PSO’s music-making ability nor was I familiar with Manfred Honeck, but I know them now and in my view this orchestra and conductor are up there with the very best in the world. This particular performance, this amazing performance, is very special indeed.

I’ve developed the dubious habit over the years of plunging headlong into a particular performance of a particular composition for a period of weeks and even months. The current star in my musical firmament was Albeniz’ Iberia and La Vega played by the great (and little-known) Esteban Sánchez Herrero. Spanish piano music is very wonderful but it is also worlds away from Anton Bruckner. The shift from Albeniz to Bruckner took time and involved a rather drastic change in aesthetic landscape, from the sensual to the austere, from the intimate to the monumental. After a very long neglect—for it’s been years since I listened to Bruckner—I suddenly rediscovered this great symphony played like I’d never heard it played before.

I do not mean to suggest that Honeck’s approach is in some sense better than that of Günter Wand or Eduard van Beinum. I’ve never compulsively sought “the” performance, that collector mentality continually adding and thinning records in pursuit of a shifting, illusory notion of perfection. I like having multiple versions of music that I find particularly nourishing. A Zen monk once entered a butcher shop and asked for the best cut of meat. The butcher replied, Every cut in my shop is the best.

Bruckner’s third symphony is program music. Bruckner entitled it “Romantic,” a reference not to romantic love but to the ideals of German/Austrian myth as typified by the operas of Richard Wagner. (Bruckner’s music sounds almost Wagnerian but it’s spiritual and emotional content could hardly be more different.) Bruckner annotated the score and sketched descriptions of rural life in those times, woods and fields and knights and castles and hunting horns. He wrote in a letter to fellow composer Paul Heyse: “In the first movement of the “Romantic” Fourth Symphony the intention is to depict the horn that proclaims the day from the town hall! Then life goes on; in the Gesangsperiode [the second subject] the theme is the song of the great tit [a bird] Zizipe. 2nd movement: song, prayer, serenade. 3rd: hunt and in the Trio how a barrel-organ plays during the midday meal in the forest.” Bernhard Deubler, an associate of Bruckner’s wrote: “Mediaeval city—Daybreak—Morning calls sound from the city towers—the gates open—On proud horses the knights burst out into the open, the magic of nature envelops them—forest murmurs—bird song—and so the Romantic picture develops further.” Good stuff, if you like that sort of thing.

The score itself was revised numerous times (the third movement completely rewritten as the Jagd [Hunt]-Scherzo). The version chosen by Honeck is from 1878/80, the definitive score used for the premiere of the symphony in 1881 when Bruckner was in his fifty-sixth year. In his program notes, Honeck goes so far as to write that the symphony might be more aptly described as a tone poem. Not merely four musical movements suggestive of loosely connected historic-pastoral scenes, but four movements telling a single coherent story. The “story” in program music is, the experts inform us, integral to the emotional content of the music, necessary, even, to a thorough “understanding” of it.

I cannot resist a digression at this point. Although I have always felt deeply attuned to classical European music, to the emotional content of harmony and counterpoint, motif and thematic development, as well as the spiritual underpinnings of musical culture, the concept of “program” music has always been problematical for me. Almost all music stands on its own, in my opinion, regardless of the composer’s intention. One can listen to this symphony over a lifetime and perhaps never suspect that Bruckner had a program in mind. (Other writers I’ve read would heartily disagree with my opinion about this.) One certainly can’t say the same of Beethoven’s “Pastoral” symphony where the music mimics nature, or something like Peter and the Wolf that is so obviously weaving an episodic story. My attitude to this and all received aesthetic wisdom is immodest but quite straightforward: does such information enhance my experience or simply clog my senses with concepts and expectation? It may be purely idiosyncratic, but I find aesthetic content invariably obviates such conceptual flotsam as programs. I was deeply moved by Bruckner’s symphony long before I knew the composer had a program in mind, and learning that he had made not an iota of difference to my experience.

Honeck’s notes are largely taken up with Bruckner’s program and how he, Honeck, sculpted the performance to clarify and reveal it. This is precisely as it should be: it is the conductor’s job to reveal the composer’s intentions. My job however is to listen to the music, to let it wash over my heart and rouse my emotions, with no reference to expectations and preconceptions. This, Bruckner accomplishes in full measure through the grandeur of his orchestral architecture, and the honesty and humility of his nature. He was a devout Catholic who composed music that most often feels both devout as well as firmly anchored in spiritual bedrock.

Bruckner is a composer of elevated and complex orchestral conception. Architectonic is the word the professionals often use when describing his music. The Fourth Symphony, although not of the almost unimaginably sustained spiritual depth and height of the later symphonies, is pure Bruckner, made of the same rich clusters of sound and high drama. (The score calls for two each of flutes, clarinets, oboes, bassoons, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings, a large gathering.) And this performance is nothing short of revelatory.

Stereo Times Masthead

Publisher/Founder

Clement Perry

Editor

Dave Thomas

Senior Editors

Frank Alles, Mike Girardi, Russell Lichter, Terry London, Moreno Mitchell, Paul Szabady, Bill Wells, Mike Wright, and Stephen Yan,

Current Contributors

David Abramson, Tim Barrall, Dave Allison, Ron Cook, Lewis Dardick, John Hoffman, Dan Secula, Don Shaulis, Greg Simmons, Eric Teh, Greg Voth, Richard Willie, Ed Van Winkle, Rob Dockery, Richard Doron, and Daveed Turek

Site Management Clement Perry

Ad Designer: Martin Perry

Be the first to comment on: Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 4