iSonic CS6.1 Pro Ultrasonic Record Cleaning System by Greg Simmons

The Workingman’s Ultrasonic

Other than wicked expensive hi-fi cables, nothing draws as many sharp opinions from audiophiles as cleaning records. Everyone has a process; everyone has an opinion; ad hominem insults abound. Folks will argue about their home brew cleaning solutions (Orange juice?!), whether or not to do a separate rinse cycle, what commercial products work, and which are worthy of derision. Does anyone remember the fad from a few years ago of wiping Elmer’s Glue onto a record, letting it dry, then peeling off the glue to reveal a supposedly pristine playing surface? Is mere distilled water satisfactory, or does truly clean vinyl require highly filtered “laboratory grade” water?

Other than wicked expensive hi-fi cables, nothing draws as many sharp opinions from audiophiles as cleaning records. Everyone has a process; everyone has an opinion; ad hominem insults abound. Folks will argue about their home brew cleaning solutions (Orange juice?!), whether or not to do a separate rinse cycle, what commercial products work, and which are worthy of derision. Does anyone remember the fad from a few years ago of wiping Elmer’s Glue onto a record, letting it dry, then peeling off the glue to reveal a supposedly pristine playing surface? Is mere distilled water satisfactory, or does truly clean vinyl require highly filtered “laboratory grade” water?

I started out with a homemade record cleaner cobbled together with a platter and bearing from a dead table, a variety of cleaning fluids, and a shop-vac with a clean cotton cloth over the nozzle. Later I bought a VPI 16.5, which was certainly more convenient to use, but I’m not sure it cleaned records any better than my homemade jobber. The VPI, which I still have, goes through arm-wands like popcorn at the movies. They crack, split, and sometimes break apart. Also, the little velvet strips on the wand pick up a lot of crud. Unless that arm-wand is changed every few records, the lips are certainly dragging that same crud across the surface of every subsequent record being cleaned, and at $42 a piece, no one changes those vacuum wands that often. It’s not a stretch to imagine that every machine with fuzzy lips suffers some of the same drawbacks.

Which leads us to the current state of the art in vinyl washing: ultrasonic record cleaning machines. When it first became available, ultrasonic record cleaning was claimed to be a hyperspace jump ahead of everything else that had come before. By using sonic cavitation in a water bath – basically, the same technology jewelers use to clean wedding rings – more of that aforementioned groove crud could now be safely removed with nothing more than energized distilled water touching the record. Every person I’ve ever spoken to in the industry – whether in recording or hi-fi – swears by these machines. One fellow I know cleans every test-pressing that crosses his desk with his KLAudio because if he has to give feedback to the pressing plant, it has to be of the vinyl, not vinyl contaminated with mold and other byproducts of the manufacturing process.

So, we should all run out to buy one and live happily ever after with clean vinyl, right? Well, not so fast. The big drawback to the fancy one-step machines is the price. Of the three most well-known, the Degritter is $3,000; the Audio Desk is $4,000, and the current version of the KLAudio machine is an eye-watering $6,500. That is not the average-Joe kind of money. Maybe when I hit the lottery.

The more affordable ultrasonic alternative has often been to buy a commercially available ultrasonic tank, then add some kind of spindle – often powered, but not always – that spins the records in the bath. These DIY machines are said to be effective but also seem a bit unwieldy, and, perhaps most importantly, they do not dry the records after the wash cycle.

There’s a market niche for an ultrasonic machine that splits the difference: sacrificing a bit of the convenience of the one-step machines while still providing all of their functional benefits and doing so at a more attainable price point. The machine needs to be effective, convenient enough that people won’t hate using it, and affordable enough that no one will go bankrupt buying it. And that leads us to…

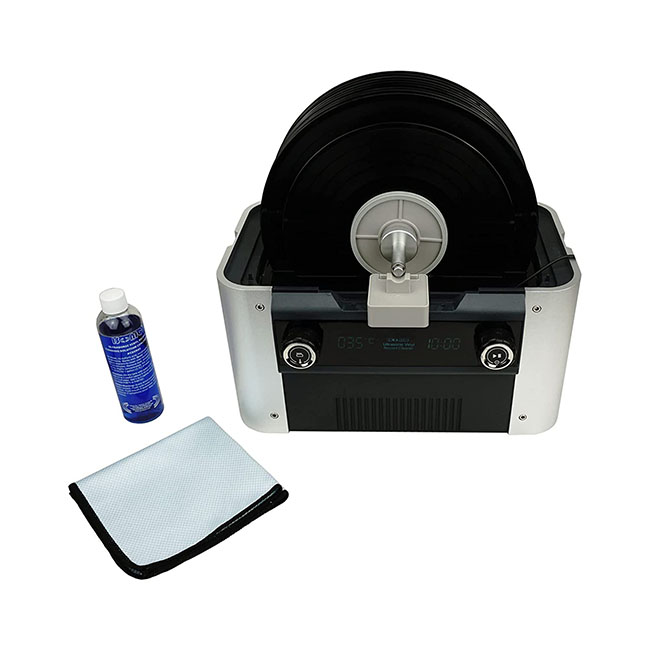

The iSonic CS6.1 Pro

The CS6.1 Pro features a relatively compact 6-liter (about 1.6 gallons) tank that can also heat the water. Having once left my entire collection of Rush albums in a bookbag on a friend’s back porch, returning to find a bag of potato chips, I steadfastly refuse to add any heat. There is a switch on the side to turn the tank on, with two knobs on the front panel to control its functions. Operation is simple. Turn it on, choose how long you want it to run – up to fifteen minutes – and hit start.

The mechanism for spinning the records in the ultrasonic bath is a hinged two-speed motor with a spindle to hold the records. The spindle lowers over the bath, resting on the other side of the tank. There is also a water filter that runs throughout the wash cycle. Both the motor and the filter share a power cable separate from the one that powers the tank. The mechanism comes with eleven flat disks with rubber gaskets that both hold the records in position and keep the labels dry. There are also additional spacers and a 45 RPM adapter. The spindle can accommodate up to ten records at a time, but this leaves only about half an inch between albums, which seems closer than ideal for good water circulation.

Operation is simple enough. Fill the water to just a little under the disk protecting the label – quarter of an inch or so – place the arched plastic shroud over the records, turn on the filter and spindle motor, then run the tank. The tank will shut itself off at the end of the cycle, though the spindle motor and pump have to be turned off manually. The machine is pretty quiet, with just a low-level audible buzz, but I wouldn’t want to listen to music with it running in the same room. I found myself starting a cycle, then going into the next room to listen to a record side, then coming back for the next step.

Drying the vinyl is where the iSonic improves on similar designs. A lever on the side of the tank releases the water, draining the tank. There is a supplied hose, but you do need something to drain the water into. The spindle motor is then switched on to its second setting, which will spin the records at about 300 rpm for about a minute and a half, stop so the user can remove the shroud for better air circulation, then start itself up again, running for another ten minutes or so. When complete, the records are dry and ready to play with nothing other than water and air having come in contact with the playing surface. Similar to the wash, during the drying cycle I went back inside to listen to another record before retrieving nice, clean records.

Ease of Use

The iSonic CS6.1 Pro is not as simple as a one-step push button, but it’s by no means onerous, and it also cleans up to ten records at a time. You do have to be careful to make sure all of the gasket discs are seated properly to protect the labels and make sure that you have an appropriate-sized vessel to drain the water into. Out of the first fifty-or-so records I washed, only one – a Cisco pressing of Dexter Gordon’s One Flight Up (Cisco CLP 7051) – got a little bit of water on the label, but just a little, and only on one side.

Soap

The iSonic CS6.1 Pro comes with a small bottle of cleaning solution with directions to add up to one capful per gallon of water. I cleaned records both with and without the detergent and found that records seemed cleaner when I did use them. The caveat is that when I did so, I ran the records through the treated water first, then re-ran them in straight distilled water to make sure I’d gotten all of the solution off the playing surface. According to Jerry Fan, this is not strictly necessary as long as the water is clean and the filter is being run, but old habits die hard.

Does it Work?

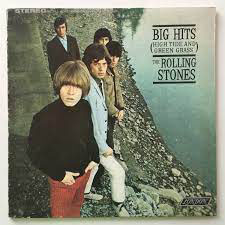

The thing that struck me about records cleaned in the CS6.1 Pro wasn’t that there was less background noise or fewer pops and ticks, though both those things were certainly true, it was the enhanced clarity and tonality of the records that had been treated. It wasn’t universal – bad pressings are bad pressings, after all – but on good recordings, treble was cleaner and less brittle with better overall detail retrieval. Bass was taut and more dimensional, sometimes ever-resolving wooliness. Subtleties and gradations – say the vibrato on an electric organ, the shimmer of cymbals, or the wooden thump of a double bass, were enhanced. Perhaps the most interesting improvement on some recordings was musical structure. The Rolling Stones Big Hits (High Tide and Green Grass (Decca TSX 101), for example, became organized on the sound stage where it had been a bit incoherent. The result of improved clarity? Probably. It’s often said that stereo recordings in the early sixties were afterthoughts following the preferred monaural versions. With this particular record, I beg to disagree.

The thing that struck me about records cleaned in the CS6.1 Pro wasn’t that there was less background noise or fewer pops and ticks, though both those things were certainly true, it was the enhanced clarity and tonality of the records that had been treated. It wasn’t universal – bad pressings are bad pressings, after all – but on good recordings, treble was cleaner and less brittle with better overall detail retrieval. Bass was taut and more dimensional, sometimes ever-resolving wooliness. Subtleties and gradations – say the vibrato on an electric organ, the shimmer of cymbals, or the wooden thump of a double bass, were enhanced. Perhaps the most interesting improvement on some recordings was musical structure. The Rolling Stones Big Hits (High Tide and Green Grass (Decca TSX 101), for example, became organized on the sound stage where it had been a bit incoherent. The result of improved clarity? Probably. It’s often said that stereo recordings in the early sixties were afterthoughts following the preferred monaural versions. With this particular record, I beg to disagree.

Success varied somewhat based on wear, the quality of the pressing, and other factors, but on many recordings, the improvement was not subtle. This was true of sixty-year-old monaural sides, new high-quality reissues, and run-of-the-mill rock and roll records of the seventies and eighties.

Old Records

Among the first records I cleaned was my two-LP set of the Beethoven “Choral” Symphony conducted by Wilhelm Furtwangler (His Master Voice, ALP1286 & ALP1287), both British first pressings from 1955. I knew the man who bought them new, so I know that he took good care of his records, and these two were rarely played. They’ve always looked pristine, but after cleaning them multiple times with a variety of solutions on the VPI they still had a bit of background noise and the odd tick. After the bath, first with the supplied detergent, then with a second cycle of straight distilled water, all of that was gone; just clean, clear, really quiet vinyl. As a monaural recording I generally play these records with the Miyajima spirit mono cartridge and they sounded great that way, but I also tried them with my Lyra Delos, figuring that the stereo cartridge would reveal any grunge left in the grooves, but there was little if any. That is impressive on a sixty-seven-year-old record.

Among the first records I cleaned was my two-LP set of the Beethoven “Choral” Symphony conducted by Wilhelm Furtwangler (His Master Voice, ALP1286 & ALP1287), both British first pressings from 1955. I knew the man who bought them new, so I know that he took good care of his records, and these two were rarely played. They’ve always looked pristine, but after cleaning them multiple times with a variety of solutions on the VPI they still had a bit of background noise and the odd tick. After the bath, first with the supplied detergent, then with a second cycle of straight distilled water, all of that was gone; just clean, clear, really quiet vinyl. As a monaural recording I generally play these records with the Miyajima spirit mono cartridge and they sounded great that way, but I also tried them with my Lyra Delos, figuring that the stereo cartridge would reveal any grunge left in the grooves, but there was little if any. That is impressive on a sixty-seven-year-old record.

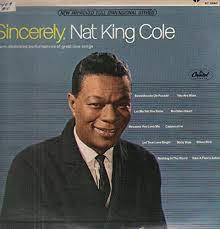

Another success story was Nat Cole’s Sincerely (Capital T-2680), a posthumously released 1966 lap through a bunch of saccharine sweet love songs with all of the excesses of the era: strings, crooning background vocals, and the like (this one is a guilty pleasure). Once cleaned, small details emerged: On one track, a low tone behind Nat proved to be a bass clarinet; massed background vocals now had individual singers, and the like. There is some wear on this record, but the clarity of the music was enhanced.

New Records

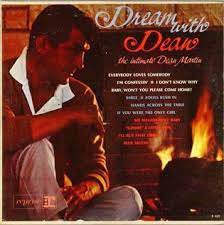

At Capital Audiofest this year, Dean Martin’s Dream With Dean (Reprise R6123 1964, Analogue Productions AAPP 076-45) was in heavy rotation. I’m certain I heard it played in at least four separate rooms and I liked it, so I ordered a copy. This is a simple, mellow production of Dean’s big tenor voice backed by – among others – jazzers Barney Kessel and Red Mitchell. Unfortunately, like so many new records, there was some persistent background noise (*Ordinarily I would have sent this one back, it was expensive after all. But in the name of scientific discovery…), so into the tank it went. The first time through, the tank had only distilled water in it, and it helped, but the background noise persisted. The second time I added a cap of the concentrated cleaning solution, then followed that with a second trip through fresh distilled water. It did eliminate the background noise during the music, even in the really quiet passages, but the lead-in and dead wax was still left with a little a bit of rush, so I’m going to put that down to the pressing. Damned good recording, though!

At Capital Audiofest this year, Dean Martin’s Dream With Dean (Reprise R6123 1964, Analogue Productions AAPP 076-45) was in heavy rotation. I’m certain I heard it played in at least four separate rooms and I liked it, so I ordered a copy. This is a simple, mellow production of Dean’s big tenor voice backed by – among others – jazzers Barney Kessel and Red Mitchell. Unfortunately, like so many new records, there was some persistent background noise (*Ordinarily I would have sent this one back, it was expensive after all. But in the name of scientific discovery…), so into the tank it went. The first time through, the tank had only distilled water in it, and it helped, but the background noise persisted. The second time I added a cap of the concentrated cleaning solution, then followed that with a second trip through fresh distilled water. It did eliminate the background noise during the music, even in the really quiet passages, but the lead-in and dead wax was still left with a little a bit of rush, so I’m going to put that down to the pressing. Damned good recording, though!

Middle Aged Records

We can’t leave out representation of the billions of pop-music records pumped out in the 1970s. A true success story with the CS6.1 Pro was a grungy-looking copy of War Greatest Hits (United Artists UA-LA648-G), a throw-away record from a church rummage sale. Prior to cleaning, the album was harsh, wooly, and just thoroughly mediocre, even after multiple cleanings with the velvet lips. The ultrasonic bath made all the difference. There is still a bit of wear-related groove noise between tracks, but it’s so low-level that it does not intrude on the music in any way. All of it gained clarity, and the bass lost all the fuzziness in favor of tight, punchy definition, which is of paramount importance on a funk record. “Lowrider” just throbs. This is a ‘wall-of-sound’ production, so no one should be looking for hi-fi soundstaging tricks, but the improvement was notable. Everything now sounds clear, clean, well-articulated, and funky.

We can’t leave out representation of the billions of pop-music records pumped out in the 1970s. A true success story with the CS6.1 Pro was a grungy-looking copy of War Greatest Hits (United Artists UA-LA648-G), a throw-away record from a church rummage sale. Prior to cleaning, the album was harsh, wooly, and just thoroughly mediocre, even after multiple cleanings with the velvet lips. The ultrasonic bath made all the difference. There is still a bit of wear-related groove noise between tracks, but it’s so low-level that it does not intrude on the music in any way. All of it gained clarity, and the bass lost all the fuzziness in favor of tight, punchy definition, which is of paramount importance on a funk record. “Lowrider” just throbs. This is a ‘wall-of-sound’ production, so no one should be looking for hi-fi soundstaging tricks, but the improvement was notable. Everything now sounds clear, clean, well-articulated, and funky.

Other Considerations

No piece of equipment is perfect, and the iSonic does require some accommodation. First, because water has to be poured into and drained out of the tank with every cycle, there is the potential for spillage and splashing. I did – in a boneheaded example – pour water into the tank without making sure that I had first closed the drain valve (only once, thanks). Not wanting to damage anything in my listening room, I relegated use of the CS6.1 Pro to the garage which is the next room from my man cave. The garage is clean enough, but even so I have to take care to keep the machine covered when not in use.

No piece of equipment is perfect, and the iSonic does require some accommodation. First, because water has to be poured into and drained out of the tank with every cycle, there is the potential for spillage and splashing. I did – in a boneheaded example – pour water into the tank without making sure that I had first closed the drain valve (only once, thanks). Not wanting to damage anything in my listening room, I relegated use of the CS6.1 Pro to the garage which is the next room from my man cave. The garage is clean enough, but even so I have to take care to keep the machine covered when not in use.

Another thing to consider is how thirsty the CS6.1 Pro is. With straight distilled water – no detergent – I found that there was visible flotsam in the water after four or five cycles, even with the filter running. That’s an indication to me that it’s time to change the water. Distilled water is cheap – about a dollar a gallon – but you can go through an awful lot of it with this machine, especially with a two-step detergent and rinse. In fairness though, I’m sure water consumption is not unique to the iSonic.

The final concern I had was whether it was working its best with a full spindle of ten records, which leaves only about half an inch between disks. My gut tells me that spacing the records out – say a max of five – gives the cavitation process a little more breathing room to work its magic. Even so, that’s still five times as many records as the fancy one-step machines, which is good.

Conclusion

Thinking back to my youth, the first person I ever witnessed trying to clean a record was my mother, dragging a damp Kleenex over her classical records on Dad’s Garrard Lab 80 turntable (Lint City, folks!). We’ve come a long way from that.

This is my first experience using any type of ultrasonic record cleaner and the results are quite good. The iSonic CS6.1 Pro certainly does clean records, and lots of them. The ability of ultrasonic cavitation to clarify music on familiar recordings is really impressive. No machine can work miracles: records that are worn, scratched, or poorly pressed, will not suddenly become reference recordings. But, even on those records, getting the gunk out of the groves can make them significantly more listenable. Also noteworthy, it does an audibly superior job of cleaning records when compared to my VPI 16.5 with its fuzzy lips of crud.

As the only ultrasonic machine I’ve had the opportunity to work with, I can’t make any claims about whether the iSonic CS6.1 Pro is any more or less effective than any of its competitors, but the feature set of iSonic CS6.1 Pro nicely splits the difference between the really expensive one-step machines and DIY gear. It scores points for the convenience of being able to clean multiple records at the same time, and scores even more points for the genuine advantage of being able to dry those records as well; all with nothing but water and air touching the grooves. Plus, it does all of this at an attainable price point. It’s made a marked improvement to my listening experience. If you’re looking for an affordable ultrasonic machine the iSonic CS6.1 Pro is worth checking out.

greg simmon

Specifications:

iSonics CS6.1 Pro – Specifications

- Price: $999

- 48 kHz ultrasonic cleaning

- 6 liter water capacity

- Compatible with 12”, 10” and 7” LPs and 45s.

- Ten LP capacity

- In-tank 1mm water filter

- Separate speeds for washing and drying records.

Greg’s Associated Equipment:

Analog Front End

SOTA Sapphire turntable w/Audio Creative Groovemaster III Tonearm

Rek-O-Kut T12h turntable w/Karmadon 12” viscous damped unipivot tonearm

Technics SL-1200 M3G w/SME 3009 Improved Fixed Headshell tonearm

Lyra Delos cartridge

Miyajima Spirit Mono cartridge

Soundsmith Otello cartridge

Audio-Technica OC/9-III cartridge

Audio-Technica AT33Sa cartridge

Digital Front End

C’mon. We live in the analog stone age around here.

Amplification

Cary SLP-98P preamp w/ phono stage

Parasound JC5 power amplifier

Aurorasound SP-03H step-up transformer

Lyric Audio PS-10 MC/MM phono stage

Loudspeakers

Verity Audio Fidelity Encore

Cabling

Finley Audio Cirrus interconnects, speaker, and power cables.

Zentara Reference interconnects and speaker cables.

A variety of other wires from Nordost, Cullen, AudioQuest and MIT.

Accessories

AudioQuest Niagara 1200 power conditioner

Tice Box power conditioner

Nordost Sort Kones AC vibration dampers

Mapleshade Audio Rack

Stereo Times Masthead

Publisher/Founder

Clement Perry

Editor

Dave Thomas

Senior Editors

Frank Alles, Mike Girardi, John Hoffman, Russell Lichter, Terry London, Moreno Mitchell, Paul Szabady, Bill Wells, Mike Wright, Stephen Yan, and Rob Dockery

Current Contributors

David Abramson, Tim Barrall, Dave Allison, Ron Cook, Lewis Dardick, Dan Secula, Don Shaulis, Greg Simmons, Eric Teh, Greg Voth, Richard Willie, Ed Van Winkle, and Rob Dockery

Music Reviewers:

Carlos Sanchez, John Jonczyk, John Sprung and Russell Lichter

Site Management Clement Perry

Ad Designer: Martin Perry

Be the first to comment on: iSonic CS6.1 Pro Ultrasonic Record Cleaning System by Greg Simmons